A downgrade that says more about politics than credit

The Moody’s downgrade marks the official end of the US’s AAA era. After S&P cut in 2011 and Fitch in 2023, the latest move brings all three major rating agencies into alignment: the US is now a AA1-rated sovereign with no “perfect” stamp of approval. The rationale is simple enough—a $2 trillion annual deficit, rising interest costs that now eat up 18% of tax revenues, and no political consensus to reverse the trendUBS.

But markets, it seems, have already priced in America’s fiscal slippage. According to UBS, the downgrade is a “headline risk”, not a structural shock. Most global investors don’t rely on credit ratings to hold Treasuries, and central banks continue to value US debt for its liquidity, not its rating. The downgrade may briefly push yields up—UBS expects a 10–15 basis point bump, as after the Fitch move—but not trigger a selling waveUBS.

What’s changed since 2011 is not the debt profile, but the narrative. The first downgrade was political dynamite. Today, it’s more like political wallpaper. Lawmakers have learned to shrug. Investors too.

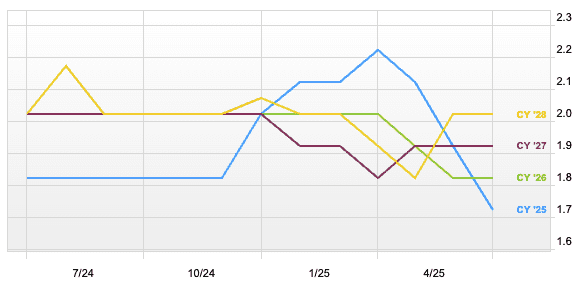

US Real GDP Growth Estimates – Calender Year Trend

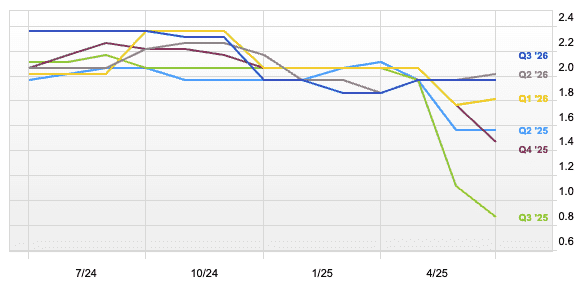

US Real GDP Growth Estimates – Quarterly Trend

What it means for portfolios: income, not panic

UBS’s read is clear: don’t sell the news—buy the yield. The downgrade, if it lifts rates, creates an opportunity to lock in durable income. The firm favours medium-duration USD bonds (around 5 years) and expects yields to fall again into year-end. For long-term portfolios, US Treasuries still represent the lowest-risk USD asset besides cash.

Equities, meanwhile, have already moved on. While Monday saw a mild pullback—S&P 500 down 0.95%, Nasdaq off 1.32%—UBS expects attention to shift quickly back to tariffs, budget negotiations, and growth expectations. Structural trends, like AI earnings and infrastructure spending, remain in place.

The dollar may be more vulnerable. UBS continues to recommend that investors with excess USD cash sell rallies, noting that dollar strength is unlikely to persist if deficits widen and the Fed becomes more active in managing bond markets.

The political backdrop: fire and forget?

The timing of the downgrade is awkward. Just days before Moody’s decision, the House Budget Committee advanced Trump’s sprawling tax package after last-minute changes appeased fiscal hawks. The “One, Big, Beautiful Bill”—a bid to extend the 2017 tax cuts—is precisely the kind of legislation that Moody’s flagged as riskyUBS.

And while the downgrade itself may not rattle markets, it brings fresh scrutiny to Washington’s fiscal deadlock, particularly as tariffs begin to bite. Trump has warned of renewed levies against trading partners that “don’t negotiate in good faith.” Walmart has already warned of price hikes, and consumer sentiment is sliding: University of Michigan’s index hit its second-lowest level ever, with 75% citing tariffs as a major concernUBS.

With no major economic data on the calendar, markets will parse Fed speeches and political signals. But unless bond yields spike sharply or consumer spending cracks, the downgrade is likely to remain what UBS calls it: a media story, not a market one.